If you aren’t at all interested in melodeon fingering layouts then look away now. You have been warned.

My last blog post of 2012 is on an interesting idea. Regular readers may remember that I wrote a little-understood post on classifying accordions a little while ago and mentioned in that post the possibility of Chromatic, Bisonoric, Button Accordions. This I defined as an accordion which uses buttons, having different notes on push and pull and based around a chromatic scale. There haven’t been any such accordions built, but the subject of this blog post is one possible idea.

The Loomes Chromatic, invented by the noted folk musician and melodeon expert Jon Loomes, is a hexatonic accordion. This means that rather than being based around the diatonic scale (which has seven notes to the octave), it is based around the whole tone scale, which has six notes to the octave. Regular readers may recall that the Hayden-Wikki Layout that I have on my Impiliput is based on the whole tone scale, as is the Janko Layout, which I have talked about before. The Loomes layout is an attempt to fit the whole tone scale into a bisonoric instrument.

There are several advantages to this approach. The first is that with more than one row, a bisonoric layout based on the whole tone scale would have every note of the chromatic scale, more than most diatonic accordions. The second is that because it has six notes to the octave rather than seven, the fingering remains constant across octaves. On the standard diatonic accordion, the push sequence along a row repeats on every fourth button, but the pull sequence repeats on every fifth buttons. This means that the fingering on each octave gets progressively different, which catches the beginner out very easily. It also limits the range of the instrument, since there are only really two and a bit usable octaves before the offset becomes awkward. Of course, if you have a standard two row diatonic accordion then the fingering on a particular direction is constant across octaves, since the relationship between rows is the same. A whole tone instrument does not suffer from this problem however, as both the push and pull sequence would repeat on the fourth button. This means no range limitation bar that imposed by the reeds themselves.

Jon, in his original idea, envisaged a two row instrument, with each row separated by a semitone. If you want, you can think of this as the equivalent in the whole tone scale of a D/D# melodeon, as the relationship between D and D# on the principal octave is the same as on that (rare but interesting) system. He has paired it with 24 melodeon basses, without thirds.

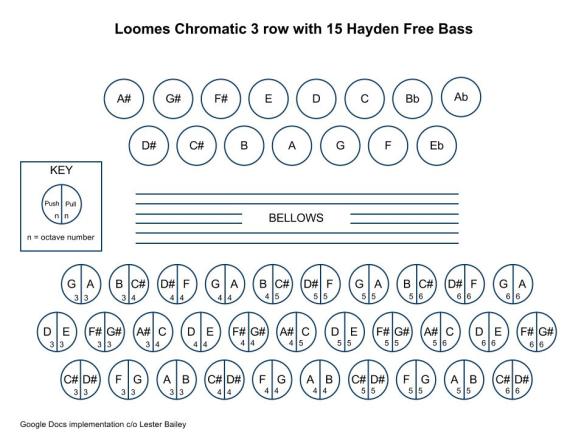

Below is my interpretation of his idea. Mine is the equivalent of an A/D/G, as A, D and G are on a single diagonal in the same direction. My original idea when designing it was to make it easier for a quint player to pick up, as some of the note relationships are the same. In reality though, it is an ‘outside in’ system (starting on the outside row and switching in), whereas Jon’s version is an ‘inside out’ system. A C#/D/D# equivalent can be found here. I leave it to the interested reader to work through the patterns. I’ve paired it with a fifteen free bass Hayden-Wikki system, just as an example, although I’ve got other ideas about what would be the best bass layout for it. Thanks to Lester Bailey for the google docs templates (click here for more).

The main competition to this system, in terms of bisonoric instruments that play in any key, is the B/C/C# or British Chromatic Accordion. This was played by the great Sir Jimmy Shand and is today played by John Kirkpatrick, amongst others. I also play it, albeit not terribly well compared to that august company. I think that the Loomes offers a few advantages over the B/C/C#. In particular, the three rows mean that major and minor chords for every scale can be played on the right hand (which is not possible on the B/C/C#). This is a substantial advantage for those interested in harmony. There are six reversals (notes which can be played in either direction), down from the B/C/C#’s eight, but both G and A have reversals, which is not the case in the B/C/C#. Learning two different fingerings (one for tonic pull and one for tonic push) will get you all twelve major scales, whereas on the B/C/C# you need to learn five. Of course, there are alternate fingerings which will make certain passages or intervals easier on both systems, but crucially, there isn’t the scale of difficulty of different keys on the Loomes that there is on the British Chromatic.

I believe that the Loomes Chromatic has a lot of potential. It can play with equal facility in every key, with huge potential for harmonic exploration. The fingering is regular and almost isomorphic (a truly isomorphic keyboard would need four rows, at which point the weight and bulk would be uncomfortable). It is similar enough to existing systems that it wouldn’t be too difficult to learn. The fingering does not limit the range, giving greater flexibility over the number of buttons. It uses one less reed set per octave than a diatonic box. I want one.

If you are interested in making, converting or commissioning a box of this system and want to chat about it then I’d love to hear from you. And if you have any queries about the system or disagree with any of my conclusions then please do comment and I’ll do my best to answer.

Happy New Year!

A superb analysis of the system – I love the right hand, but being an 18 bass JMC player, I find the 24 bass ‘spiral’ of the original system much more intuitive …

I’d be very interested to have a crack at mocking this up somehow, possibly using one of those .. Ern. Roland (!) devices… :-)

Heh, well opinions differ on bass ends, we all know that! Jon’s one is a lovely example of the type, but I am most definitely not an 18 bass player. If you have a crack at mocking it up I’d love to have a play with it…

Being a Hayden duet ‘player’ who’s interested in entering the world of isomorphic bisonic instruments, this is the best idea I’ve seen so far. Looks really interesting.

The other option is the Atzarin system, which is based on the diminished seventh chord scale up and down the rows or the chromatic scale across them. The Atzarin is basically a bisonoric chromatic button accordion, the Loomes is basically a bisonoric Janko keyboard. Obviously to a Hayden player, the Loomes would be easier, as it employs the whole tone scale which you’d be already familiar with.

Thanks for posting that up Owen – I love your blog – I think this is probably the most interesting one to date for me at least.

I’d love to have a try at this system as it looks like it should be fairly easy for a D/G player to adapt to. Obviously it’s a much bigger leap of faith to actually get an instrument that plays that system to give it a go.

Apart from seeing if the standard major keys are simple enough to learn over 6 buttons for the scale rather than 4 (the push pull pattern is the same) – I’d love to see how it would fare for the pull minor keys and also whether the push-pull attack and sound of the quint box system could be maintained with the more complicated fingerings and the unisonoric bass. Those are things that it’s harder to imagine just looking at a keyboard diagram. Another thing hard to imagine without actually playing an instrument is how comfortable/ergonomic the shapes needed for most music actually feel under the fingers.

On paper though, it is the best system by a mile I’ve seen to attempt to meld chromaticism with a push-pull instrument. Well done John!

Hi John, nice to hear from you! Glad that you’ve been enjoying the blog and pleased to see that you are as interested in this system as I am.

There are a few different fingering patterns that you could use for major scales. If we take G major, we could start on the inner row on button four (push) and proceed to i4pull, i5push, middle 6pull, m7push, m7pull, m8push, inner 7push. This is a very ungainly fingering, as you’d run out of fingers, but preserves most of the directions that are on the D/G.

The alternative is to start on the outer row and proceed o5pull, o6push, o7pull m6pull, m7push, m7pull, m8push, o8pull. This is rather easier on the fingers and I think that it would be quite comfortable but it doesn’t retain the order of push and pull.

If we use Jon’s original row relationships then you get the push sequence of the former with the shape of the latter, which might be the best of both worlds. With Jon’s original, G, B, D#, D, F# and A# would all be tonic push, whereas with mine it would be F, A, C#, D, F# and A#. The others would be tonic pull. The disadvantage with John’s system is that the note relationships aren’t as similar to D/G/A as they are with mine. I’ll leave it to you to work out exactly which keys you’d want to play in, how you want to play (inside out or outside in), how important the direction is to you and therefore which version of the layout would best suit you. I’m not sure which one I would chose yet. Just like the quint layout, there are many possible versions for different uses.

I don’t think that this box will have the same drive and power that the quint box has, but then it isn’t designed to. There isn’t such a thing as a box with all the attributes of a quint box which can play in any key, because it is the fact that it can’t play in every key that gives it the style and grace that it has. Every time you make a change to an instrument you gain something and you lose something. I would however anticipate this system to be quite bouncy. In particular, consider that the tonic and major second for every key bar E, G# and C can be played on one note. Simile fifth and sixth for every key bar A, C# and F. I would expect this box to be bouncier on average than say a three row with odds and sods on the inner row, if you take it over every key, and probably bouncier on average than a B/C/C#. So this is probably about as close as you’ll get, until someone else comes up with another idea.

As you say though, we won’t know until someone tries learning it. I would predict, based on my own experiences with my D/Em and my B/C/C# that the reversals will mean that there are lots of possible fingering patterns and learning them sufficiently in order to get the desired effect (i.e. bouncy or smooth) will take time. And only time will tell how easy it is to change and adapt the fingering to suit the tune, which is almost impossible to see from a diagram.

I really wish that I could learn this thing, but sadly I have no money at all at the moment. Otherwise I would try to get one. Perhaps in a few months I’ll be able to rip something together, you never know. If I do then I will report my findings back to the blog. If you decide to give it a go then please stay in touch, as I’d love to hear how you get on.

You’re absolutely right – I’ve looked at the Aztarin system on paper and tried to work out tunes and the Loomes system is much more intuitive to me.

Oddly enough, the original draughts of this layout were based on quint relationships – I shifted one row up a bit to make it more b/c like. The first version of this (back in about 2007 ish) was a design for Julie Fowlis who wanted a box for singing with in her favoured keys, B, Bb, F, F# etc – but it needed to be as small as possible (hence two row) because she’s slightly built. The first version was a 2 row with home keys of G/A and D/E on inside and outside rows respectively and a 24 bass monotonic LH laid out according to cycle of 5ths. While you can do a fair amount with the two row version, to be truly useful you need a third row (A/B home button) reversing the push pull pattern as at that point all chords become possible in either direction – by extension a 4 row version would give you more consistent fingering but by this point the damn thing weighs so much that it no longer fulfils the original design brief and you might as well have a continental chromatic!

I tell a lie, 3 rows makes 1/2 the chords possible – you need all 4 for full chordal chromatic nonsense….then again, you do have a lot of options using the LH in combination with the RH…..blimey. I had all this worked out once! Cheers, J

With three rows you have all of the major and minor chords and some of the sevenths on at least one direction with both directions for six keys. I don’t think that you need them all both directions, as it takes 4 rows and I agree, you almost might as well have a CBA, unless you are militantly bisonoric. The three row version I think is a competitor to the standard three row melodeons, which are gaining in popularity. It gives you more options across the board in a more logical way without being conceptually difficult. Compared to a three row CBA there is little to differentiate them, but compared to a G/C/# I think that this comes out on top.

There are I think 12 possible Loomes Chromatic layouts. One with rows a semitone apart (the one on your website), one with rows a fourth apart (the one that I’ve presented here) and one with rows a sixth apart, which I haven’t played with but I think would be unusable. These three offsets can have the two whole tone scales the opposite way round (middle row D or middle row G) and can be reversed (D push on the middle row or E push on the middle row say), making (I think) twelve possibilities all in all. Each has their own characteristics.

The matter of bass end is even more one of personal preference. I love your circular bass end, but I think that I’d probably have some sort of Hayden inspired one.

Just a note that paragraph 2 of my first reply to this post is rubbish, since I’ve thought of many more Loomes layouts since then.

For something meeting the original brief then I think that 2 rows with 15 free bass would be the best option, creating an instrument with the sound of a melodeon but similar in function to a duet concertina.

24 melodeon basses would also be a tall order and need either a very complicated mechanism or a slightly less complicated but still far from simple mechanism with a ton of reeds. IMO, free bass dovetails very nicely with the right hand layout from both a theoretical and practical point of view.

I would agree with the bass end analysis, especially if the instrument is intended to be small. I would also submit something like the Darwin layout, although that is very focussed on particular keys. I still think that the three rows justify themselves. If only two rows are used then Jon’s original layout (semitone) is far preferable to my quint one.

It seems to me that this layout is somewhat analogous to a C system CBA layout, and that means that there is (probably) a B system variant available. The inside row would become the outside row, the outside row would become the inside row, and the outside and inside rows would shift “up” or “down” (towards or away from the floor) so that, on any press or draw, you would get three ascending semitones if you start on the inside row and go out and down diagonally. As currently laid out, you would start on the outside row, and go IN and down to get an ascending set of semitones. The advantage of this variant is that chromatic riffs are done from a more relaxed and natural hand position, while everything else is about at the same level of difficulty. This mirrors (IMHO) the superiority of B system CBAs (chromatic button accordions) over C system boxes. For those of you who do not follow, take a three row box (if you have one handy) and put your first finger on an inside row button, and your second and third fingers on the second and third row, but diagonally closer and closer to the floor. This hand position would be used when playing any bits of “chromatic run” (bits of music that use all 12 notes of the scale). As given above (the last layout shown above in this blog), the corresponding hand/wrist position would be a little more “twisted”. The most important thing to remember is that once you go to three rows in a system like this, each layout has a mirror image that might be less or more advantageous. Something to think about?

You are quite right, the layout that I have given is the equivalent of the C system. I’ll admit to not having thought about this. An example of a B system equivalent would be an A/C/D# whole tone, i.e. rows a minor third apart (you can draw that one out for yourself!) and on first glance, appears to have most of the advantages of the quint system that I’ve drawn out above. However, whereas the quint layout allows all 12 major diatonic scales to be played without moving the hand or changing fingers, the minor third layout only allows 6 to be played this way (push on outer two rows). In this way it is similar to the chromatic system, which also allows 6 to be played this way, but on the push on the inner two rows. The quint system is the only one that I have found thus far that allows scales to be played on the pull without awkwardness.

I think then that the minor third layout offers advantages for chromatic playing over the chromatic layout, since playing a chromatic scale would be that much easier, but for those intending to play diatonically over chromatically the quint layout is preferable.

Pingback: It has been too long | Music and Melodeons

Pingback: The Atzarin Accordion | Music and Melodeons

Pingback: Harmonetta Bass | Music and Melodeons

Pingback: Inside and Out Part 7 – The Atzarin Accordion | Music and Melodeons

Pingback: 19 Tone Equal Temperament | Music and Melodeons

Pingback: Happy New Year! | Music and Melodeons

Pingback: The Atzarin System | Music and Melodeons